2025 Reading in Review

I've been busy

Hello readers! It’s been a while since I’ve written here. I have probably had a mix of factors — life events, your own fluctuating feelings and moods, the whole weird world situation — in my life similar to yours going on in mine, most of which haven’t been conducive to me writing in this thing steadily.

But, I still read a lot. I thought, perhaps as an entryway to posting more here, I’d do a set of pithy reviews of the many books I’ve read this year, starting with the ones I did before the last book I wrote about, and maybe even going back and filling in some ones I read earlier this year but didn’t review. Among other things, it’ll be the end of the year quite soon, and I also want to post about this year’s Mithra Awards, top 10s, bottom 10, etc. So without further ado-

Peter’s Books of 2025, Part 1

Anatole France, Penguin Island (1908) - This is the story of European civilization told through via the story of penguins on an island who are given souls because a blind monk “converted” them, and God figured “well, gotta give ‘em souls!” They go on to recapitulate the whole darn shooting match, down to a penguin Dreyfus Affair. Honestly got tedious, I kind of like the Sarah Anderson version of the religious plus penguins better. ***

Gary Indiana, Resentment (1997) - This was one of the best books I read all year. In fact, I got hung up trying to write about it… Gary Indiana was a novelist, journalist, and critic who first gained prominence in New York in the eighties. Resentment is, among other things, the story of a Gary Indiana type – gay, smart, burnt out by bummers ranging from the AIDS crisis to his petty career woes – losing his mind slightly as he tries to cover a case that is, more or less, the Menendez Brothers trial, which was heavy in the news in the nineties before a certain running back bumped them off the LA-murder-media-spectacle pedestal. Here’s my favorite ruminative section in the book-

Everyone agrees there is something monstrous and awesome about the Martinez case, but some people have different reasons for thinking this than others. Jack hasn’t given it much thought at all. In Jack’s mind, the Martinez case figures among a dozen current events buzzing in the zeitgeist, things you hear about without really wanting to, Jack believes that events can be tricks that keep your mind off some unchanging structural flaw in human organization, circus acts designed to numb critical scrutiny. Something hidden, a conspiracy or some sinister condition of things. Jack’s forever trying to figure such things out, attach a diagnosis, settle a meaning. Jack thinks that everything that happens hides something else. Since losing faith in dialectical materialism, Jack’s inclined to analyze things in occult terms, flirting with the belief that thirteen men control the world, that planetary configurations determine random-looking events, that each person has an astral double whose actions are unseen, metaphorical, the true text of his life. In his dreams he is a butterfly who dreams about being Jack.

Seth believes the Martinez case resembles a large underwater rock, magnified by immersion, with something wriggling underneath it: blind albino fish, possible, or eyeless eels that have grown to unbelievable length, or prehistoric flintheads encrusted in mossy crud. He thinks the Martinez drama probably illustrates something but doesn’t mean anything, that you couldn’t use it, for instance, to figure out the kinship system of the primitive Bororo or extract from it the chemical steps to enrich uranium. But you could turn it into a Mardi Gras float or a tableau vivant in a wax museum, serialize it into Stations of the Cross, fashion it into topiary or embroider it on exotic underpants. Seth believes it is always better for something to happen than for nothing to happen, he likes it when life speeds up and propels him through a lot of stuff he can’t make heads or tails of at the time, arranging it later into complicated stories, yarns, fables, fairy tales, novellas, poems, jokes, verbal sculptures of any sort that bend in his mouth like putty.

Indiana died last year. I can’t imagine seeing the ways he discusses two fringe figures losing it becoming the main ways people look at the world and make decisions made him happy. *****

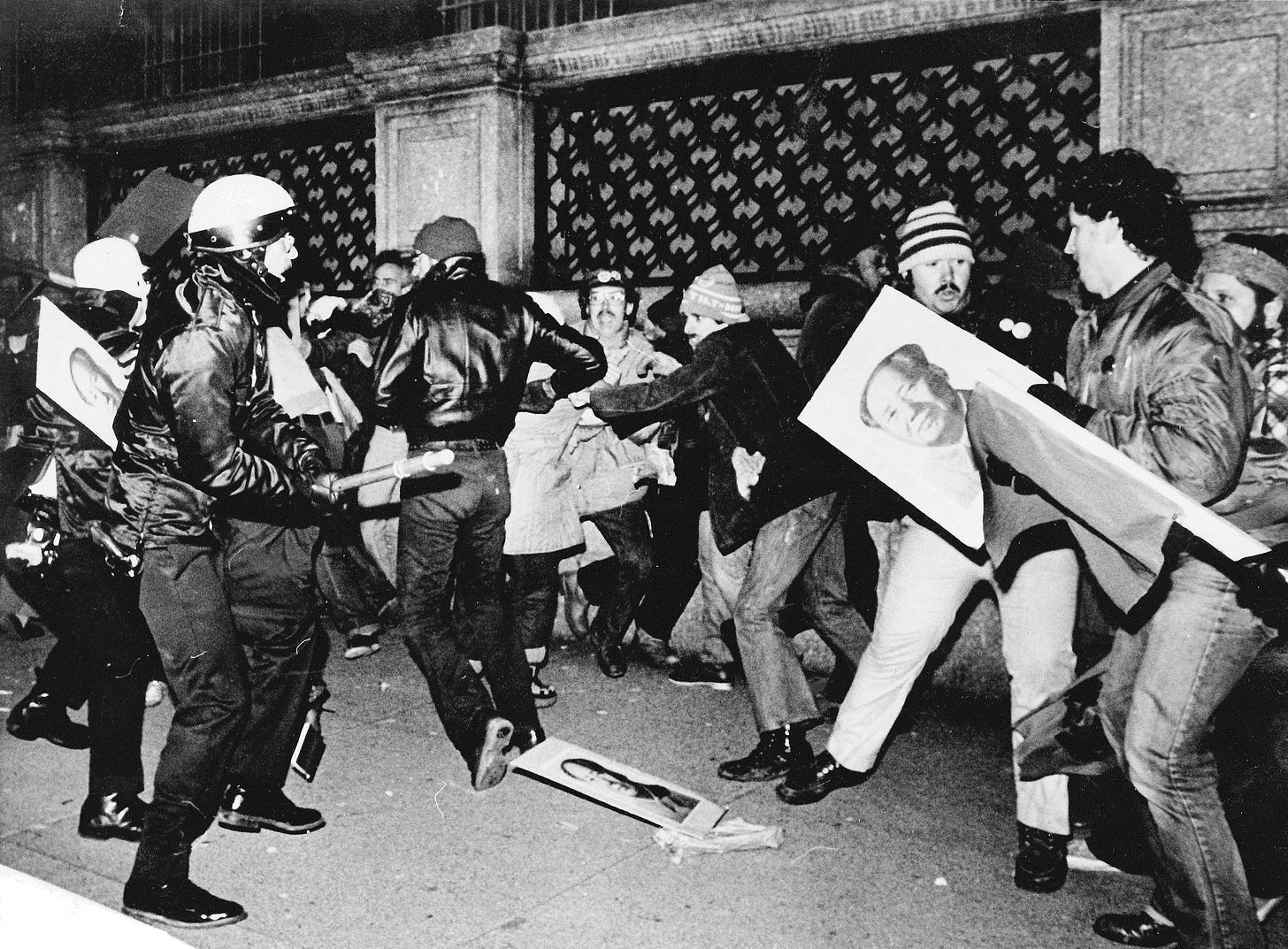

Nathan Hill, The Nix (2016) - Oh boy… what do I remember about this? A complicated domestic plot involving a feckless academic throwing his life away via MMORPGs, the mother who abandoned him as a child, said mother’s hidden past interacting with some iconic moments of sixties radicalism, something involving a curse from “the old country” (Norway)... I remember it being decent but too neatly resolved for my liking. ***’

Ian McGuire, The Abstainer (2020) - An old friend recommended this some time ago, and I finally got around to it. I’m glad it did, it was fun. A story of Fenians and cops in 1860s Manchester, murder and muddled loyalties in the fog and gaslight. It involves a classic character often done poorly, but here done well- the enforcer from the oppressed side working for the oppressor. Worth reading for fans of crime fiction and historical fiction if they like it crime-y. ****’

Frederic Jameson, Postmodernism (1990) - Remedial reading for me, likely should have read it during comps all those years ago. Impressively erudite, but god help me if I retain much. Probably that’s partially down to the way the kernel of the book – the “postmodernism is the cultural expression of late capitalism” bit – is already pretty known in my circles (I think David Harvey did it better, though). ****

Avery Dame-Griff, The Two Revolutions (2023) - This is a history of the transgender internet. The trans community as we know it is hard to imagine without the internet, to the point where transphobic reactionaries mutter darkly about it and act as though there’d be no trans people without it (seemingly forgetting they were shitty babies about the whole thing well before Tim Berners-Lee did his thing). Interesting look at the earlier history, what’s changed and what hasn’t. ****

Aaron Leonard, Meltdown Expected (2024) - Probably not the Aaron Leonard volume to start with. He’s a historian who has done a lot of well-regarded research on sixties-seventies radicalism and the state’s repression of same, and I’d like to read more of that. This is more of an overview of how shit was actually crazier in the seventies, in many ways, than in the sixties, which is true but I would have gotten more, I think, from his more research-heavy stuff.

Megan Abbott, You Will Know Me (2016) - Megan Abbott mostly writes the sort of thrillers that have covers that most men would pass over, but they shouldn’t. I dig her stuff- it’s tight, mean, creepy, and sharp. Among other things, she knows how to pick unsettling areas of supposedly normal life for settings, especially this one- the world of elite child gymnastics, with all the insane dedication, cultlike community, and grotesque policing of children’s bodies that go along with it. It was a rough ride, but commendable. ****’

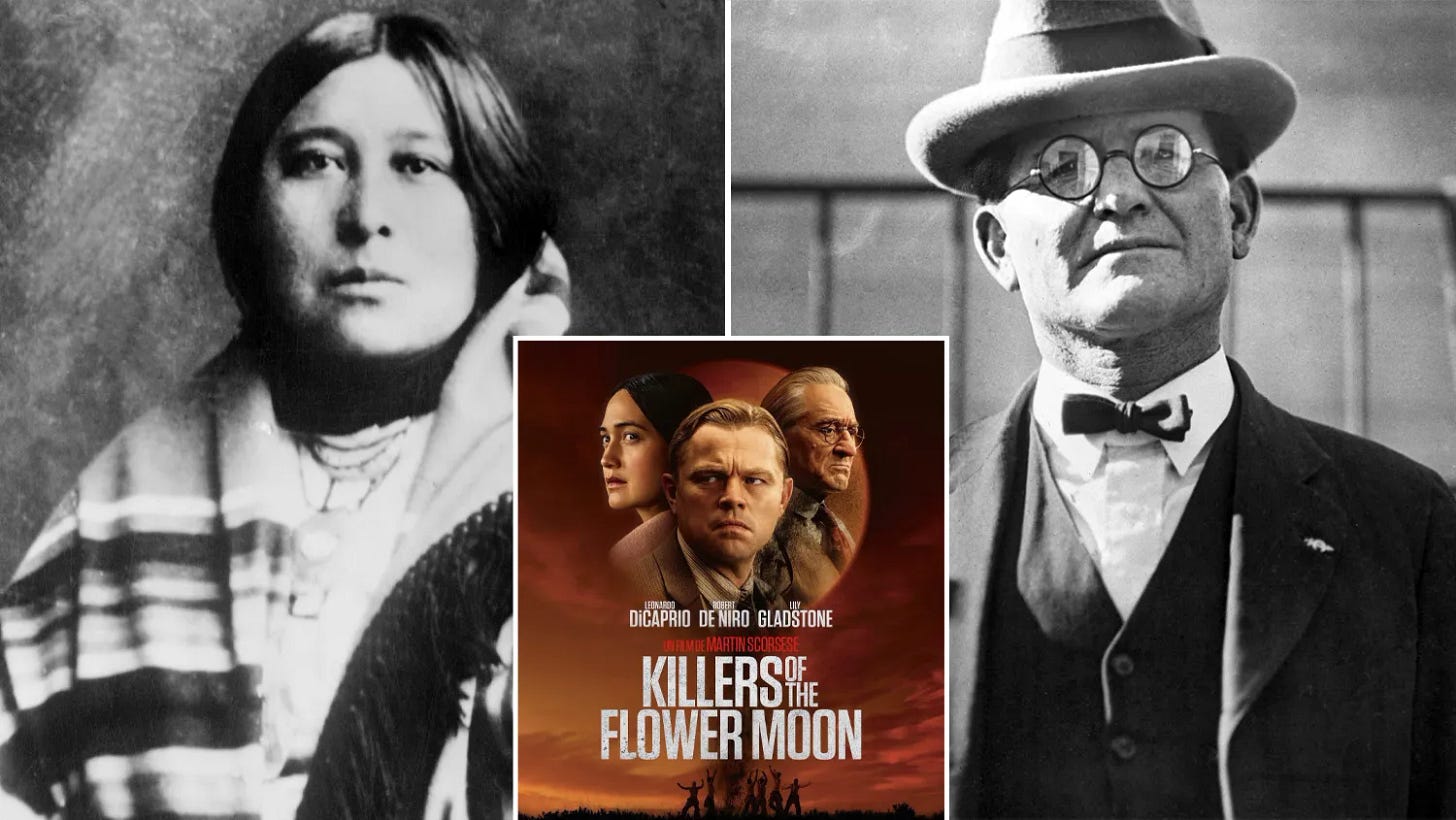

David Grann, Killers of the Flower Moon (2017) - I had seen the movie before listening to this. In many ways, I think Scorsese did a better job dramatizing the story, but like… of course he did. The book is also good. What an awful story. ****

Alexei Yurchak, Everything Was Forever, Until It Was No More (2005) - See, I’ll likely need to reread this if I ever need to talk about it intelligently. I gotta remember to do reviews! Even just internal ones. I noted it as ****

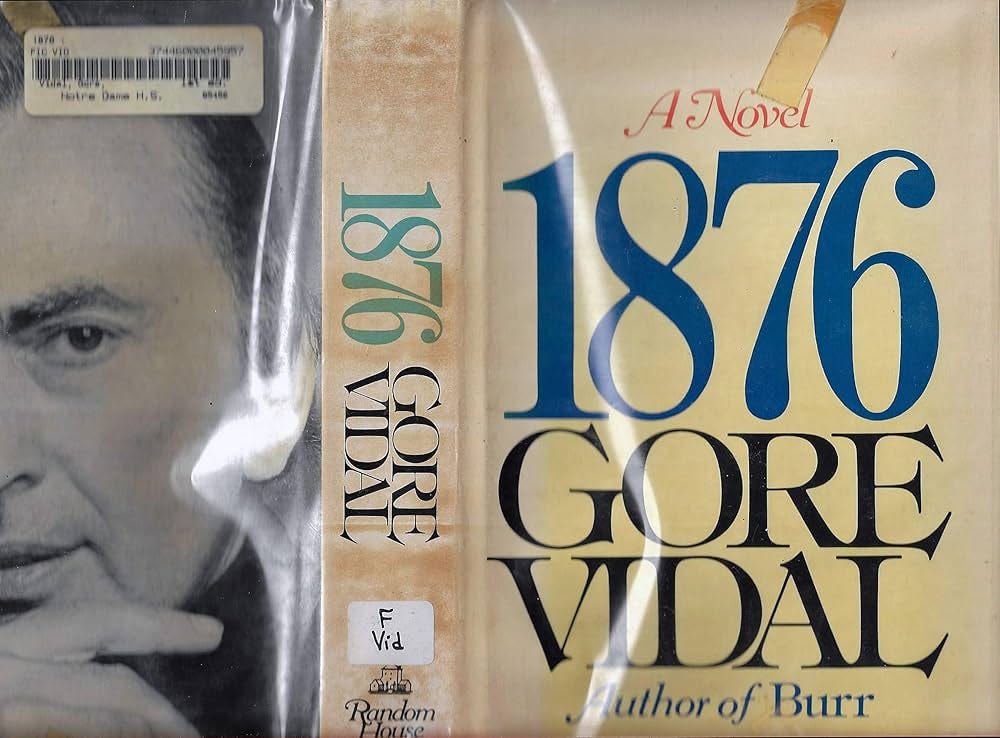

Gore Vidal, 1876 (1976) - This one was fun- the third installment in Vidal’s “Narratives of Empire” series, set in the titular year, the launch of the Gilded Age. Vidal brings back his narrator from Burr, a lot older and more crotchedy. Truth be told, this choice does make the book less enjoyable than its predecessor, to me anyway. And, if I can be partisan, however many things Ulysses Grant screwed up as President, no one’s going to convince me that any of that was less important than supporting Reconstruction, even to the relatively limited extent he did. Vidal takes what he was taught in school about Reconstruction for granted, and it shows a much less charming side of the old posthumous-winner-of-various-literary/political-pissing-contests than we’re used to. Still- a good read. ****

Anyway… that’s it for now. There’s plenty more where that came from.

Mithra chooses to occlude her face today-