Of Edgelord Artifacts

A review of "Neo-Nazi Terrorism and Cultural Fascism" by Spencer Sunshine

Hey all-

My current plan for this space is to write in it when I have something to say. If it looks like I’m going to do that a lot, I might set up the paid tier again. For now, here’s a review of a book that had me thinking a lot, and which will figure into my thinking and writing in the near future.

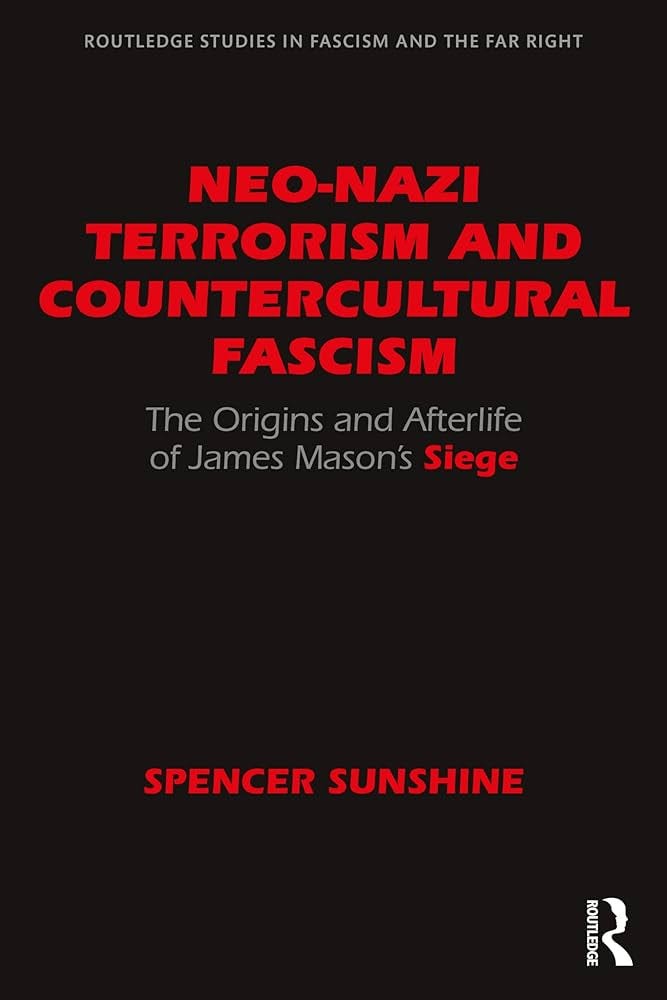

Spencer Sunshine, Neo-Nazi Terrorism and Countercultural Fascism: The Origins and Afterlife of James Mason’s “Siege” (Routledge, 2024)

Well… here we are, again. Donald Trump has been elected President. The right, an especially vicious, ignorant, belligerent right, seems ascendant worldwide. Nobody knows what they should be doing but seemingly everyone with a platform is trying out various vain postures. Those of us who would genuinely fight for a better future don’t know where to start. We are back at the “shit or go blind” stage of early 2017, just with everything a few years older, a few years more decrepit.

We see the same discourse about the far right, too, except (again) staler, dumber, palpating exhaustion. Yeah, sure, let’s trot out the excuses, try to see the good side of these ghouls and grifters, and always, always throw the most vulnerable — migrants, the homeless, trans people — to the wolves in the hope it will propitiate… ah, who’s anyone kidding? When Zuckerberg or the New Statesman, to cite two talkers my phone has seen fit to flap in my face recently, go through the motions, po-facedly learning “lessons” “the left” refuses to learn, do they hope to actually gain anything for anyone other than themselves? For the culture at large (Zuckerberg) or the left (NS)? No- they want a line of shit to keep chattering on and, maybe, a pass from the purges- “we’re not woke! We’re not woke! Kill the PMC, chop the tall lattes!” Fat fucking chance, guys.

Anyway… I remember early 2017 well. I was eight years younger and more energetic. But, I remember what did us a bit of good then, and I think it will do some good now. Fuck a “vibe shift.” Let’s get real. Refuse the notion that all because there’s no media consensus on what is real and what isn’t, that there isn’t anything real (or a hell of a lot of things that aren’t). Will rigor save us? On its own, no. And maybe nothing will. But it’s better than wallowing in the fake.

To that end, I want to talk about a book that discusses some of the most extreme — sometimes in deed, always in affectation — areas of the right, in a sane, grounded way that sticks to sources. I’m referring to Spencer Sunshine’s monograph from last year, Neo-Nazi Terrorism and Countercultural Fascism. Sunshine has worked as an anti-fascist scholar/organizer for a while now.

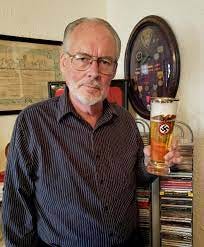

Spencer has a source, a good one that, apparently, nobody or almost nobody has bothered to mine before: the big collection of letters that James Mason decided to give to an archive at the University of Kansas. James Mason is an American neo-nazi best known for writings collected into a book called Siege. In it, Mason called for racists to abandon all hope of political change through movement-building in favor of more or less random violence. Violence — the more destructive and arbitrary the better — would put strain on “the System,” hastening a supposedly-inevitable apocalyptic crash. The crash will then allow the true master race — the whites — to emerge from the ruins victorious. According to this logic, violence and destruction, in general, are good. Mason is also known for his admiration of serial/cult killers ala Charles Manson, who he promotes in his writings, his advocacy for Satanism, and an extensive record of sexually abusing minors. He is still alive, unfortunately, residing in Colorado, taking Nazi visitors, and, almost certainly, working as an informant for one or multiple law enforcement agencies.

Siege became a shibboleth for portions of the right over the last decade, including some that have produced mass casualty attacks. “Siege-pilled” became a phrase in online fascist circles, and if it described you it meant you, like Mason, weren’t interested in movement politics anymore and had embraced full on war on the system, or at least retreat into hermit-like survivalism. It didn’t always mean a lot, when people said that; it could be an expression of frustration, and given that most online fascists are dumb and young they often enough find another way to posture later. But then, there has been actual deadly violence inspired by Siege, and actual groups that form to encourage members to do the sort of “‘lone’ wolf” attacks Mason encouraged.

Sunshine had planned, he writes, on writing an article on Siege, the kind of thing with which researchers like him are often tasked, a sort of explainer. That’s when he found out how extensive the Mason archive in Lawrence is (did Mason, still sadly alive, donate his papers because he didn’t want to schlep them from one welfare hotel — he lives off government assistance — to another? Who knows). Mason was an inveterate correspondent who saved everything, and he sought out and kept records of every ephemeral Nazi group he contacted. Sunshine now had a lot of material, more than he ever anticipated having.

Is “history of the book” still a thing? It was still a bit of a thing when I started grad school, but fading- big eighties Umberto Eco vibes, digging into the odd early modern predecessor artifacts of books as we know them. Well, the more one looks at Siege, the less it looks like a conventional book (like Sunshine’s, say). It’s a compilation of newsletters that Mason sent out to a small list of followers over the course of years. That’s not that unusual- we know about edited essay collections. But Mason kept going back, over the years, adding commentary to his own commentary, shuffling the order of the writings as he adjusted his own vision and allegiances, creating new and different editions for various publishers and eventually taking advantage of the self-editing possibilities presented by computers and the Internet.

Mason poured his whole being into Siege, it seems. He wasn’t a leader, or even a fighter. A chickenhawk (in more ways than one), he never took his own advice- he neither meaningfully fled the system (which continues to support him via Social Security and, one suspects, informant paychecks) nor picked up a gun or a bomb and took his run. He could argue he did better than that, inspiring however many dolts to do so. But Siege didn’t become a shibboleth by proposing readers undertake agitprop. We know what it is because it advocates terror for its own sake, and Mason never answered his own call. Hell, Siege would probably have even more legs had the guy been gunned down by the Feds after doing some atrocity, given the same publishing trajectory (more on this below).

But that wasn’t, isn’t, Mason. Leftists who’ve attended even a few meetings will recognize the type- Mason (so humbly!) doesn’t see it as his job to lead, by example or otherwise. It’s his job to be right, the one guy with the correct line, and to not let anyone forget it. From the correspondence Sunshine reviews, Mason lived ever hopeful of his strategy’s adoption by this or that hick thug fuhrer-manque, and ever regretful as he wrote them off when they fall short of his vision. All of this petty scorekeeping can be found in the pages of Siege along with the gore-hungry ranting for which the internet kids come to it. Siege is like Mason’s entire political life turned not just into some final document, but into a palimpsest- and one that sometimes shows the mark of other hands.

Sunshine, armed with his extensive record, goes over every turn in Mason’s associations and writings, cross-referencing it with his correspondence, carefully laying out when, where, and in line with whom aspects of Mason’s thought emerged, one layer of the Siege palimpsest at a time. It can get heavy, I’ll admit, keeping track of various low-grade neo-Nazis, their organizations all reshuffled combinations of the same half dozen or so words (“National,” “Front,” “Vanguard” etc etc). I enjoyed it, because I can appreciate the technique involved and because I find the movements of ideology freaks interesting in and of themselves. Antifascist researchers are used to this kind of thing, too. Fascists are cagier than other ideologues, hiding who they are, what they do, and what they believe behind one or another respectable front or just behind masks and uniforms. Hermeneutics for the contemporary antifascist has to involve social network analysis, records searches, matching distinctive features between social media posts and photos from fascist actions.

It’s a curious kind of exegesis, to throw another GRE word into the mix. At the end of the day, most people don’t especially care about evidence. If you say someone’s a fascist (or, to take another outcome of similar reporting, a sexual predator), the listener to the claim usually wants to believe, or disbelieve, or not care, based on whatever ideas with which they came to the situation. And for most people, people without the power to do anything about a given charge, the only change they know how to make is to what they think about the accused, where the subject now stands on some spectrum of (often imagined or parasocial) relationship. Friend or foe? When we want to elevate judgment above opinion or gossip — if we want to prove something — we often borrow methods from fields with material stake in rigorous (if not always just, or right) judgment: the judiciary, the sciences, the insurance industry. People develop more sophisticated tools for situations when something important is on the line (of course, people can also pretend to use those tools in a performance of rigor to sell a lie or an obfuscation).

The forensic gaze can be off-putting. Here’s something I’ve noticed: have you ever found a clique where individuals within said clique are really comfortable with anyone, especially anyone from outside, calling them part of the clique? Or with speaking for it? There must be some, but I struggle to think of an intellectual or artistic movement in modern times where the people within the movement embraced the label with comfort and without irony. The artistic movements of the twentieth century either denied their own existence, or made various ironic distancing gestures (or post-ironic closening gestures, like Italian futurism acting like squadristi, but that’s not naive behavior). The closest thing I can think of is various types of fandom, and even there people can get hinky- “oh, I just like (cultural object), and go to conventions sometimes, I’m not one of those crazy fans.”

The quality of the offense people can take when you say they, or someone they admire or identify with, is part of a scene or milieu, really is unique, a kind of affected wounded innocence that can, if given sea room, turn into a fucking improvised pseudo-philosophical stemwinder, the kind of thing that’d cap an American Beauty-style Oscar-bait movie, on whether anyone is ever associated meaningfully with anyone else at all… “people are just PEOPLE, MAN!” … especially if there’s no legal paper trail establishing otherwise. People don’t like even the word “milieu” (why do you think I’ve been repeating it so often?) or really any other word for this stuff- “clique,” “scene,” “circle,” “group,” all are imprecise and most of them ring unpleasantly in the forensic context. It’s especially hard in the arts. Artists and their hangers-on don’t like being pinned down conceptually or organizationally. Postwar fascism shares with any sort of art movement with claims to be avant-garde and/or transgressive an interest in resisting efforts to illuminate and examine their claims, actions, and membership, on any terms other than theirs.

We see this shared affinity in action in the back half of this work, where the History of the Book that is Siege slides down the literary digestive tract from writing material to editing and publishing (given its frequent revisions and re-releases, this was not a clean break). There’s a good chance that Siege would not exist as a book at all if it weren’t for the involvement of what Sunshine calls “the Abraxas Circle.” This group of musicians, writers, and publishers includes several people with names that might not be household ones, exactly, but who reach well beyond the usual Nazi circles. Most notable of these are: Boyd Rice, best known as an industrial music pioneer; Michael Moynihan, also a musician and the music journalist who wrote Lords of Chaos, the best-known book on Norwegian black metal; and Adam Parfrey, recently deceased, the founder of publisher Feral House. Moynihan and Parfrey, especially, were instrumental in turning “Siege” into a published book, into an artifact that could be purchased and, more to the point, uploaded onto and downloaded from the internet, something upon which one could be “-pilled” - “Siege-pilled” being a phrase I’ve seen used often.

Several interests drew these men into a nexus in the late 1980s and continuing into the 1990s. Listing these tendrils of culture goes a good ways toward providing an index to “extreme culture” as understood in the last two decades of the twentieth century and first decade of the twenty-first, what I’ve been coming to call the age of waste. James Mason obsessed over violence, and did so out in the open, praising spree killers and serial killers especially for the extremity (and pointlessness) of their violence. Specifically, Mason saw Charles Manson as a near-divine figure, a prophet of the race war to come (the amount of times “Mason” and “Manson” show up in the same paragraph doesn’t get any easier to read over time). The two men corresponded. Mason always refused the clean-cut aesthetic of much of the far right, even the uniformity of the skinheads, in favor of wearing his distinctly non-family-friendly vision on his sleeve. He obsessed over the occult and Satanism, UFOs, and sexual violation, including that of minors.

All of this was the stuff of the “extreme culture” of the time. Another “scene” that its participants would almost certainly rather dance in a minefield than admit existed, let alone that they were part of it, except of course to twit interlocutors right in their nosy noses with superior knowledge, extreme culture existed in “underground” music and art scenes and in publications passed by mail and hand, and eventually online. Adam Parfrey, who seemed to have been as cagey a cultural entrepreneur as… well… as never got extraordinarily wealthy… anyway, he did as much to define extreme culture in his time and place as anyone with his compilations, Apocalypse Culture I and II and in other Feral House offerings. Mason featured in the first Apocalypse Culture book alongside a cast of other cranks.

For the reader acclimatized to the existence of hateful people who write hateful things, what most offends about Apocalypse Culture and many other works from the extreme culture milieu is the sheer determination to offend on the part of the editors (less often the authors of the works they collect, who were often pursuing their own odd agendas). And this is less personal — “why is this grown, educated man trying so hard to offend me?” and more general: “surely this grown, educated man could be doing something better with his time than this.”

A very interesting book I read a year or so back, Jordan Carroll’s Reading the Obscene, argued that more than fighting for civil liberty, editors and publishers such as HL Mencken and Hugh Hefner who challenged obscenity and censorship laws did so with a class agenda: educated, middle-class or above men such as themselves should have the right to sophistication enjoyment of material that would confuse or rile up the rubes, women, and poors. Moreover, they thought men like themselves should act as curators and gatekeepers, protecting the interest of sophisticated readers from both contamination from the lower orders and from unsophisticated censorious bluestockings. What we see with Parfrey (who was from a similar class background from a Mencken or a Hefner) is a kind of inversion of the same dynamic. Parfrey and his friends were, supposedly, superior to “the herd” because they could “handle” reading Nazi rantings, depictions of gory murder and abuse of children, agitprop of all kinds, with sangfroid and appreciation, somewhere on the spectrum between ironic and post-ironic. A class agenda had degenerated into a clique agenda (though with notable class overtones which grew stronger as some of the principals, especially Moynihan and Boyd Rice, got old).

The interest that really united Parfrey and his friends with Mason was admiration for Charles Manson. Michael Moynihan, another racist fascist who uses his own political inutility and artsy obfuscation to mask the sort of man he is, worked with Mason to edit “Siege” into the artifact we have today, published by Parfrey’s Feral House. Moynihan, for a while, was selling Charlie Manson’s rantings and Qaddafi’s little green book (wonder how many tankies bought the latter from this “traditionalist” fascist?) alongside his lame music. For his part, Parfrey (who frequently pointed to his own Jewish background as supposed proof that he couldn’t be a nazi/fascist/bigot/whatever) certainly prattled a lot of racist bullshit in his correspondence with Mason. A favorite selection of mine which Sunshine finds in the archived correspondence is where Parfrey says he published writings by Black and Latino (ruder terms used in original) gang members as cover for getting real white philosophers like Mason into print. Middle class swot try-hard- I bet Mason thought LA gangbangers were the best sort of people of color, helping advance society towards its cleansing collapse.

Genuine bigotry, or buttering up an old racist so as to sell his book and make some money through shocking squares? Who cares? Parfrey’s dead. From what I read, it sounds like Parfrey was, for much or all of his life, a very common sort of upper middle class racist, the (sub)cultural elitist who supposedly hated all races equally… but you could tell some were more equal than others, shall we say. We can also dispense with the idea that Parfrey or his friends were genuine free speech absolutists. Even if we assume he was joking or lying about only publishing non-Nazis as covers for publishing Nazis, Parfrey was perfectly happy to try to disrupt the publishing and propagation of work from his own ideological/cultural enemies, including Sunshine himself. I have friends who knew and liked him a lot, I have friends who knew him and thought he was a dickhead. In terms of his cultural legacy, Feral House published a lot of garbage and also some good books, books I own and like (and books Sunshine owns, he hastens to say in his introduction), books that might not have seen print otherwise. Of course, “Siege” likely would have never been published as anything other than gun show samizdat if not for Moynihan and Palfrey, either. I’m less interested in some “blood on hands” sense than I am in getting at what fascism and “edginess” meant for cultural actors 1979-2008, what it means now, and what that tells us both for history and for contemporary antifascist practice.

I’ll say this: one thing that drew the Abraxas guys and James Mason together was an interest in Satanism and the occult. More than this being further (pointless, try-hard) edginess, I think it’s quite fitting to the circumstances. Magic works on obfuscation- that’s where the word “occult” comes from. It works on making use of the environment and the interlocutor’s blind spots and desire to believe to advance the idea that the performer is capable of more than he actually is. At higher levels, it involves much greater technical chops than shown by most of the Abraxas crowd (they say Boyd Rice has talent as a musician but it all sounds like music for an edgy video game to me). But at the end of the day, they all communicate more from hiding and lying, and from acting hurt and misunderstood when called to account, than they do through their sweaty performances. Anton LeVay was a carnival barker, and fascist satanist Abraxas clique guy Nick Schreck married his fascist daughter. That’s where the meaning is in their version of edgy culture: the joys and sorrows of the carnival barker. The contempt of the “mark” makes as good an emotional ballast for fascism as any- though not for any of the more impressive kind of fascist, I have to say.

As I’ve written elsewhere, “edgy” was a choice adjective for a time where things seemed flattened: the flat world of Tom Friedman’s version of globalization, the flat time of Francis Fukuyama’s end of history, the flat(ter) hierarchies of emerging tech companies, the flat affect popular in areas of culture, etc. If we want to stretch that metaphor, we now have growing numbers of people who think the world actually is flat. What happens when yesterday’s edgy gesture becomes today’s gospel truth for who knows how many brain-scrambled chuds? “Nothing good” appears to be the consensus, and nothing more sophisticated than that, yet.

Well, I’ve rambled long enough. I intend to get into stuff like this much further in this year’s Birthday Lecture, where I will explore trajectories of cultural figures from the “edge” cultures of the age of waste and how they adjusted to the world post-2008. Spencer Sunshine is an antifascist researcher, a much more accomplished one than me. His primary interest is in exploring the etiology of a book that crops up again and again connected to acts of terror and foiled plans for such. I think he also wanted to put a final nail in the coffin of the idea that Moynihan, Parfrey, and associated edgelords weren’t fascists, or at the very least fascism-sympathetic in the nineties (and refusing to own up and recant since). He probably knows well that lies don’t really die, that as long as there’s any interest in these guys someone, somewhere, will still cover for them- either that, or “fascist” will cease to be an accusation to refute, which given that even Donald Trump uses it as an insult (and no, that doesn’t mean we should stop using it). But that’s part of the deal with telling the truth. Rigor is a personal discipline as well as a tool for finding truth. If nothing else, it will go a long way towards avoiding making an embarrassing spectacle of yourself, as more or less everyone Sunshine profiled here does, again and again.

I’ll be back again when I’ve got something to say. In the meantime, here’s the face of a cat whose dad told her she’s on to her play of sitting in my writing chair in the hopes I’ll bribe her with a treat to vacate (it worked, too, alas)